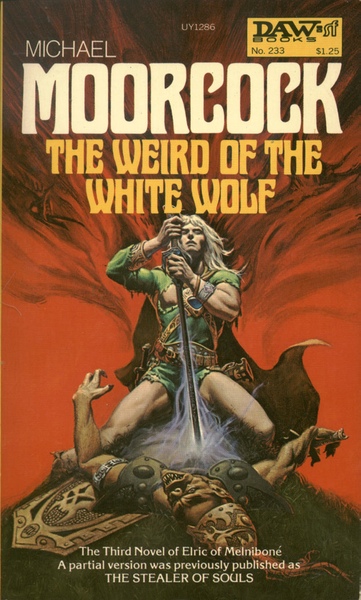

Welcome back to the Elric Reread, in which I revisit one of my all-time favorite fantasy series, Michael Moorcock’s Elric saga. You can find all the posts in the series here. Today’s post discusses The Weird of the White Wolf, published in 1977.

We are, as I and other writers at Tor have observed, well steeped nowadays in dark, brutal cinematic visions of what it means to be an heroic character. Superman lays waste to a city to save it; Batman must become the city’s scapegoat and descend into hell before redeeming himself with an act of self-immolation. Audiences and critics are, understandably, starting to chafe at these tropes; this may make the Elric saga, and The Weird of the White Wolf in particular, a bit of a hard sell these days.

This volume includes the first two Elric stories ever published, which are some of the great inversions of the standard heroic tropes of high fantasy. One way or another, the long shadow cast by Elric touches on every gloomy and doomy male SF&F protagonist making his tortured way through a world he can barely stand to live in. But you can’t really blame Moorcock for the imitations, no more than you can blame Tolkien for the Middle-Earth rip-offs. And as often happens with the originators of persistent archetypes, what really endures of these early Elric stories is their fresh and violent energy, and Moorcock’s fierce imagination.

In “The Dreaming City,” Elric returns to Imrryr at the head of a fleet of human reavers—no returning Aragorn, he only wants to kill his usurping cousin Yyrkoon and rescue his beloved Cymoril. For the rest of the city, which “fell, in spirit, five hundred years ago,” he cares nothing: he explicitly commands his allies to “raze the city to the ground.” And they do, raping and pillaging with abandon. Then, as they sail off, laden with slaves and treasure, they are attacked first by the Melnibonéan navy, which decimates the battle-weary fleet, and second by Melniboné’s ancient dragons, about which Elric had neglected to warn his allies. (Elric is, frankly, not the greatest battle-commander.) The dragons destroy the fleet utterly—save for Elric, who uses his magic to cut and run at the last moment. He even abandons his friend Smiorgan Baldhead—last seen inviting Elric to be a guest in his native land—to the flames. He hasn’t even got Cymoril to comfort him, for in his final duel with Yyrkoon, she dies “screaming on the point of Stormbringer,” forever earning him the epithet of Womanslayer. Even to the contemporary reader, the story’s bleakness is breathtaking; Elric’s losses are nearly complete, and his only remaining ally is Stormbringer—the sword that acts on him like a drug, and which quite literally will not allow Elric to cast it away.

And so on to “While the Gods Laugh,” which takes place a year after the destruction of Imrryr. Elric, now thoroughly notorious in the Young Kingdoms and making his living as a mercenary, is approached by Shaarilla, a woman of the people of Myyrrhn who, unlike the rest of her kind, lacks wings. She needs his help to acquire an ancient artifact known as the Dead God’s Book, “believed to contain knowledge which could solve many problems that had plagued men for centuries—it held a holy and mighty wisdom which every sorcerer desired to sample.” Shaarilla’s quest for the book is almost touchingly simple: eventually, with embarrassment and anger, she admits that she hopes it contains some spell that will give her wings, after which she would no longer be considered deformed by her people. Elric, however, has motives that are nothing less than existential:

Despairingly, sometimes, I seek the comfort of a benign god, Shaarilla. My mind goes out, lying awake at night, searching through black barrenness for something—anything—which will take me to it, warm me, protect me, tell me that there is order in the chaotic tumble of the universe; that it is consistent, this precision of the planets, not simply a bright, brief spark of sanity in an eternity of malevolent anarchy …

I have weighed the proof, Shaarilla, and must believe that anarchy prevails, in spite of all the laws which seemingly govern out actions, our sorcery, our logic. I see only chaos in the world. If the book we seek tells me otherwise, then I shall gladly believe it. Until then, I will put my trust only in my sword and myself.

One good thing comes out of this quest: it brings Elric together with Moonglum of Elwher, whose indefatigable buoyancy of mood provides a much-needed balance to Elric’s own melancholy, and who will accompany Elric to the very end of his saga. But the Dead God’s Book itself turns out to be the epitome of false hope, for when Elric turns back the jewelled cover of the book, it literally crumbles to dust in his hands, destroyed not by magic, but by its own great age. He and Shaarilla part ways in despair—though Moonglum, ever practical, is quick to grab a handful of the gems that fell from the book’s cover on the way out.

“The Singing Citadel” is practically a lighthearted caper by comparison. Elric and Moonglum are recruited by Queen Yishana of Jharkor (who, like Shaarilla and many other women in the saga, is immediately quite taken with the moody albino) to solve the mystery of a beautiful piece of Chaos magic—a mysterious citadel into which people are starting to disappear. That Elric is able to win both Yishana’s ardor and to defeat the errant Chaos Lord who summoned the citadel earns him the hatred of Yishana’s erstwhile favorite sorcerer, Theleb Ka’arna—and his rivalry with Elric will have consequences for some time to come.

A brief word about “The Dream of Earl Aubec,” also known as “Master of Chaos,” included in the original publications of The Weird of the White Wolf. It is effectively a prequel to the entire Elric saga, as it tells the story of the hero whose sword Elric wields in Elric of Melniboné, and in fact, in the new Gollancz edition, the story is included there instead. As part of The Weird of the White Wolf, it’s a bit of a distraction; it establishes certain facts about how the world of these stories was shaped in the conflicts between the forces of Law and Chaos, but Aubec is not a particularly interesting hero. Insofar as it works at all, it’s much better placed before Elric of Melniboné.

“The Dreaming City” and “While the Gods Laugh” are, admittedly, the works of a young man who, in 1964’s “The Secret Life of Elric of Melniboné,” describes himself as under the influence of “a long-drawn-out and, to me at the time, tragic love affair which hadn’t quite finished its course and which was confusing and darkening my outlook. I was writing floods of hack work for Fleetway and was getting sometimes £70 or £80 a week which was going on drink, mainly, and, as I remember, involved rather a lot of broken glass of one description or another.”

One could be quick to dismiss these stories as the work of an angry young man full of the angst and despair that some people specialize in during their early twenties. But there’s an intellectual and literary framework that is the Elric stories’ secret strength. Moorcock’s introduction to the 2006 collection Stealer of Souls sheds more light on what went into Elric at the time: seeing Sartre’s Huis Clos and reading Camus’s Caligula on the occasion of his first trip to Paris at fifteen, a love of classic gothic fiction like The Monk and Vathek, and Anthony Skene’s debonair villain Zenith the Albino, antagonist to pulp detective Sexton Blake. And the title “While the Gods Laugh” is taken from the poem “Shapes and Sounds” by Mervyn Peake:

I, while the gods laugh, the world’s vortex am

Maelstrom of passions in that hidden sea

Whose waves of all-time lap the coasts of me,

And in small compass the dark waters cram.

It’s not particularly subtle work. Stormbringer is quite plainly a metaphor for addiction and obsession; the real genius is the way that Moorcock makes the blade a character in its own right. When Elric tries to throw it away, it refuses to sink in the sea and cries out with “a weird devil-scream” that Elric cannot resist. Over and over again the sword continues to exhibit a fractious, malevolent personality that is as often at odds with its wielder as in his service. Elric’s existential angst may seem overwrought, but Moorcock comes by it honestly and, crucially, not solely through genre sources. And Moorcock is smart enough to leaven it with both Elric’s own ironic humour and Moonglum’s irrepressible good cheer, both of which we’ll need in the adventures to come.

Up next: Theleb Ka’arna’s vendetta against Elric continues apace, and aspects of the Eternal Champion return.

Publication Notes:

The Weird of the White Wolf includes the following four stories:

- “The Dream of Earl Aubec” also known as “Master of Chaos,” originally published in Fantastic, May 1964. Included in The Singing Citadel, Mayflower, 1970. Included in To Rescue Tanelorn, vol. 2 of The Chronicles of the Last Emperor of Melniboné, Del Rey, 2008

- “The Dreaming City,” originally published in Science Fantasy #47, June 1961. Included in Stealer of Souls, Neville Spearman Ltd., 1963. Included in Stealer of Souls, vol. 1 of The Chronicles of the Last Emperor of Melniboné, Del Rey, 2008

- “While the Gods Laugh,” originally published in Science Fantasy #49, October 1961. Included in Stealer of Souls, Neville Spearman Ltd., 1963. Included in Stealer of Souls, vol. 1 of The Chronicles of the Last Emperor of Melniboné, Del Rey, 2008

- “The Singing Citadel,” originally published in The Fantastic Swordsmen, edited by L. Sprague de Camp, Pyramid Books, 1967. Included in The Singing Citadel, Mayflower, 1970. Included in To Rescue Tanelorn, vol. 2 of The Chronicles of the Last Emperor of Melniboné, Del Rey, 2008

The Weird of the White Wolf was published as a single volume in the US and the UK:

- US Mass Market Paperback, DAW, Mar 1977, Cover by Michael Whelan

- UK Mass Market Paperback, Grafton, 10 May 1984, Cover by Michael Whelan

Gollancz publication uncertain; these stories will probably be included in The Sailors on the Seas of Fate collection, due September 2013.

Karin Kross lives and writes in Austin, TX. She can be found elsewhere on Tumblr and Twitter.